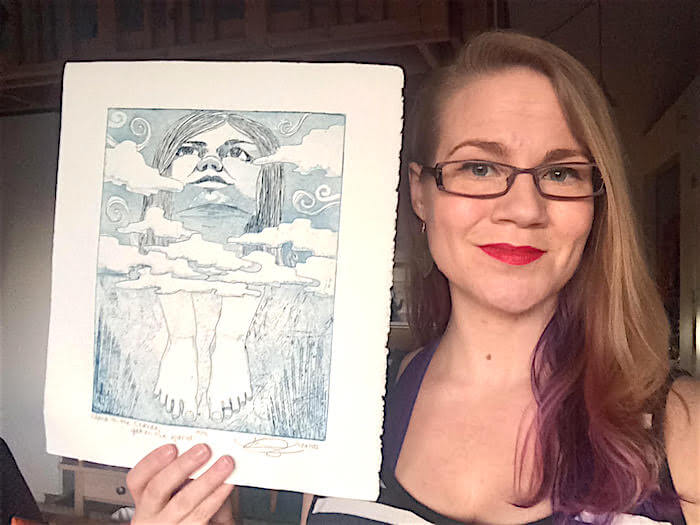

Psychiatrist Will Siu, MD, is an advocate for healing from trauma from psychedelics. Currently a therapist on clinical trials using MDMA-assisted psychotherapy to treat PTSD, he shares his insights into a very human way to heal …

When we think about trauma, we often go straight to war, physical, or sexual abuse. But as important, are the traumas of neglect, of feeling un-safe, of feeling un-loved. People think: “I don’t deserve to say, ‘I’ve suffered trauma’. But that’s BS. All of us have suffered numerous traumas in our lives.

When this trauma is unhealed and unresolved, this manifests as suffering—in our bodies and in our beings. And so we find strategies to cope. Depending on our genetic make-up, our family history, and our place in society, this might look like a cluster of symptoms that we call OCD, PTSD, or addiction. I don’t think about these as disorders. They are simply what our body and mind are doing to try to protect us. There’s nothing wrong with us—these symptoms just show us that there is a trauma to be healed.

We’ve been throwing medication at this for years, and it doesn’t work. When it comes to mental health, Western medicine has seen most success with SSRIs like Prozac for treating depression, for example. But they only work slightly better than a placebo. It’s silly when physicians say this is the answer.

In contrast, the data from trials on MDMA for PTSD, psilocybin for alcoholism, psilocybin for end of life anxiety, and MDMA for social anxiety, is better than anything else we’ve seen for mental health. But there’s still a lot of resistance to integrating these therapies, which I believe stems from a fear of these being dangerous or addictive drugs.

I also want to emphasize that the studies being done are using these substances to facilitate the psychotherapy process. It’s not the molecules themselves that are doing the healing. Rather, they are assisting the interpersonal healing process that we call “psychotherapy.”

When it comes to healing trauma, I think of the concept of “catharsis”—and old psychology term for the process of releasing, and thereby providing relief from, strong or repressed emotions. And three things need to happen for our bodies and our minds to release us from our traumas. There is a need for the intellectual memory of the trauma to be coupled with the emotional memory of it, and for this to happen in an empathic setting. Empathy is different from sympathy, when we might hear: “oh, that must have been hard for you.” It’s about really feeling that the person in front of you understands your experience. In many cases with empathy, there isn’t even a need for words.

What you’ll notice in my recipe for catharsis is that psychedelics are not in the equation. That a therapist is not in the equation. That a shaman in white linen a warehouse in Brooklyn is not in the equation. This is because we’re capable of doing this work by nature of us being human. Not that these things can’t be helpful, but thinking that one or more of these modalities themselves is going to heal you, is a mistake.

I believe that because of the way that Western culture has developed—with the breakdown of community, the breakdown of family—we’ve created the need for mental health professionals. It is possible to do this work on our own. When people are trained, there is a higher chance of healing the deepest wounds, but I don’t think it’s necessary. There are people who’ve been doing underground therapy for a long time—not that everybody does it well, including people who are trained to do psychedelic therapy. The key is to trust yourself and the way you feel when you are working with someone.

A psychiatrist named Stan Grof, who was friends with Albert Hoffman, who discovered LSD, has said: “The full experience of a negative emotion is the funeral pyre of that emotion.” This is an important way to think about healing from trauma. With psychedelic therapy, we’re talking about enhancing “negative” emotions and memories, whereas the Western approach has focused on suppressive therapies. Look at the categories of medications we use: anti-depressants. Anti-anxiety meds. We’re really doing the opposite of trying to feel every emotion through to its “funeral pyre.”

Western medicine and psychiatry are not to blame for this. It’s also an approach that represents our culture and where we are as a society. The emotions that we tend to suppress are sadness and fear. Interpersonally, and in self-help memes on social media, they’re thought of as signs of weakness. Something to be ashamed of, as if there’s something wrong with us for feeling or expressing them. I think the way we treat them medically is a result of this cultural treatment of them. Emotions like joy and anger, meanwhile, are very, very acceptable. We need to shift this if we’re going to do any real healing.

Using psychedelics as part of the Western medicine approach in doing this work is also going to take a change in society. These are evocative therapies. They’re the opposite of suppressive therapies. They evoke emotions, they evoke memories, they evoke physical symptoms. Hopefully in an environment that is conducive to healing. The term “set and setting,” coined by Timothy Leary in 1961, speaks to where you’re at personally, who are you with, and what is the physical space like. All of these elements have an impact on your overall experience.

Of course, some of these consciousness altering molecules can also be used to escape from our problems, including ketamine, marijuana, alcohol, MDMA, and nicotine. Again, it comes back to set and setting as to whether these things can be helpful or harmful. I’m also not saying these substances can’t be used for recreation, for fun, for creativity. We just need to not be fooling ourselves when we’re trying to do healing work with them.

The final piece I want to mention is integration. People aren’t focusing enough on this part of psychedelic healing, which I think of as the work that is done in the days, weeks, and months after the experience itself. In my opinion, the majority of the long-term benefits of psychedelic therapy is in the sober work that follows.

Real bravery doesn’t come from taking a third of fourth cup of ayahuasca, or five or six tabs of acid. It’s really about going back to work the following week and seeking to make peace with the coworker that irritates you. It could be calling a sibling you haven’t spoken to in nine months because you felt they aren’t as “enlightened” as you, and choosing to love them anyway. These healing interactions are truly where we find the long-term benefits of this work.

///

Will Siu, MD , DPhil, studied medicine at UCLA, the National Institute of Health in Washington DC, and Oxford University. In addition ton addition to his private practice in NYC, he is a therapist on clinical trials using MDMA-assisted psychotherapy to treat PTSD. Learn more about Will and his work HERE and follow him on Instagram.